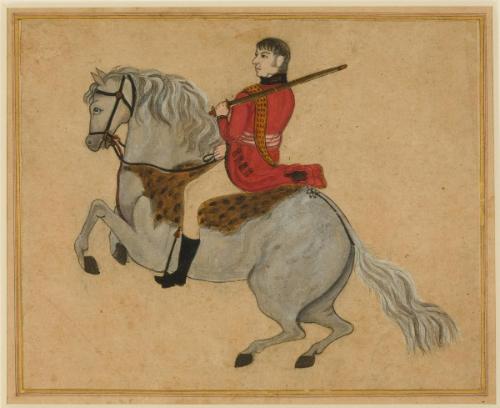

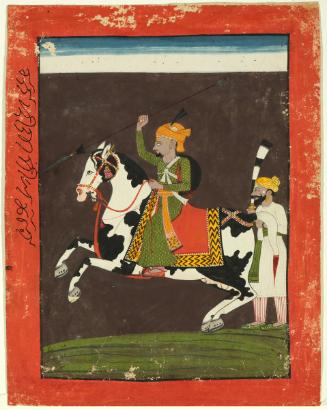

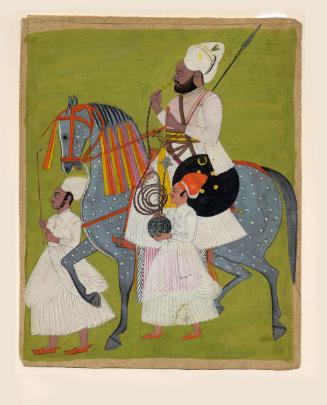

Colonel James Skinner (1778-1841) on a prancing horse

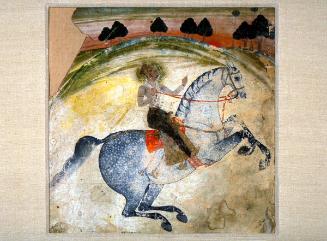

A British officer on horseback charges forward in a pose long associated in European art with conquering heroes such as Napoleon (at right). Indeed, Lt. Col. Skinner, the subject of this portrait by an unidentified Indian artist, was described by a British contemporary as “one of the bravest and most distinguished soldiers in the East India Company’s army.”

But Skinner was more complicated than the stereotype of the soldier fighting Britain’s battles in India. His father was English, but his mother Indian. Another contemporary said “he attends to the Anglican religious service on Sunday, prays otherwise in the mosque on Friday. . . . His habits are a unique mixture of European as well as Asian. . . . He speaks Persian as well as he speaks English. His mother tongue is Hindusthani.” His mixed heritage did not go unnoticed. Several contemporary observers commented on his relatively dark complexion (though this is not shown in this painting), and one noted that “he is met by his fellow officers . . . with perfect good-will, not withstanding his Eastern origin.”

Furthermore, Skinner was not just a military man. He was also, in the words of a prominent art historian, “one of the leading patrons of Delhi artists in the second quarter of the nineteenth century.” It is not known whether he ever owned this painting. By about 1900 it was in the possession of a noted collector in what is now Pakistan, and it stayed in the Pakistani family’s hands for a number of decades.

Thus what appears to be an unremarkable depiction of a standard-issue British officer turns out to contain unexpected complexities of identity and tradition.